This is a topic every guitar player should understand, but which I find many are still confused about what it means: forms and types.

So, because this is a column about what every advanced beginner and early intermediate player should know by now, review of previously learned topics is a logical and

practical necessity. You need to ensure what has been learned is fully understood and firmly planted in your memory for later reference. You will encounter problems

and you will need to have ready solutions so you won't be stopped dead in your tracks.

And if you don't know this topic at all, or find yourself confused when the subject of chord knowledge comes up, then all the more reason to go over this subject. So

pay attention!

This can mean the difference between dropping a song and keeping the song as part of your play list. And when you're writing songs, it can mean the difference between

a well crafted song and a mediocre song that just doesn't work - because you couldn't find what the song needs to be a great tune!

And if you have hopes of recording albums and touring, failing to overcome the obstacles you will confront in writing music will result in endless frustrations and

the loss of potentially great music, which means you won't achieve your goal. This is when you'll hear those horrible words; "Don't quit your day job."

So, let's dig in! A chord type is one of the following: Major, minor, dominant, augmented, diminished or suspended.

A chord form is how you play a given chord type, the fingering you use.

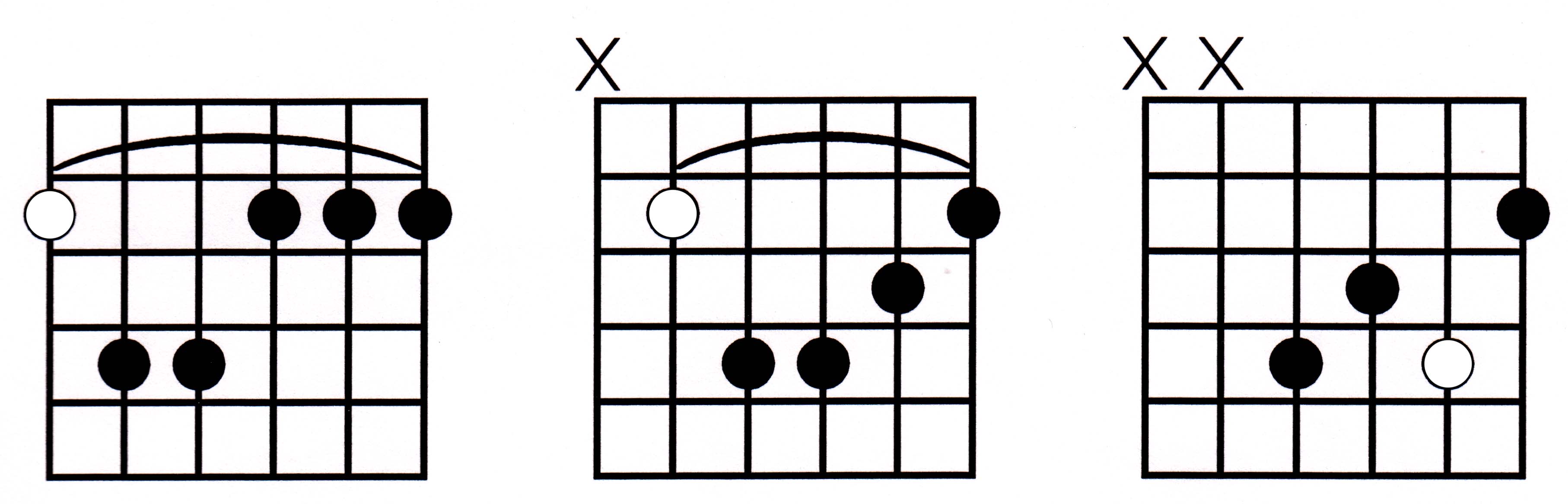

Below is a graphic of a typical Major chord, which is the "type", shown in three "forms", three different fingerings, based on a 6th, 5th and 2nd string root (yes,

in some there is more than one root tone). Note that the root tone is represented by an open circle.

In virtually all cases of moving to a different string root, the fingering will change. Therefore, the form changes, too. And in some cases, as with the third example of the Major chord, the voicing will also change. This is often due to the maj 3 interval between the 3rd (G) and 2nd (B) strings.

Just to clarify. If you're playing a G Major with a sixth string root, it is at the 3rd fret, the fifth string root would be at the 10th fret. The final example would be based on the root being on the second string at the 8th fret, which will also have an altered voicing with the 3 tone on the bottom.

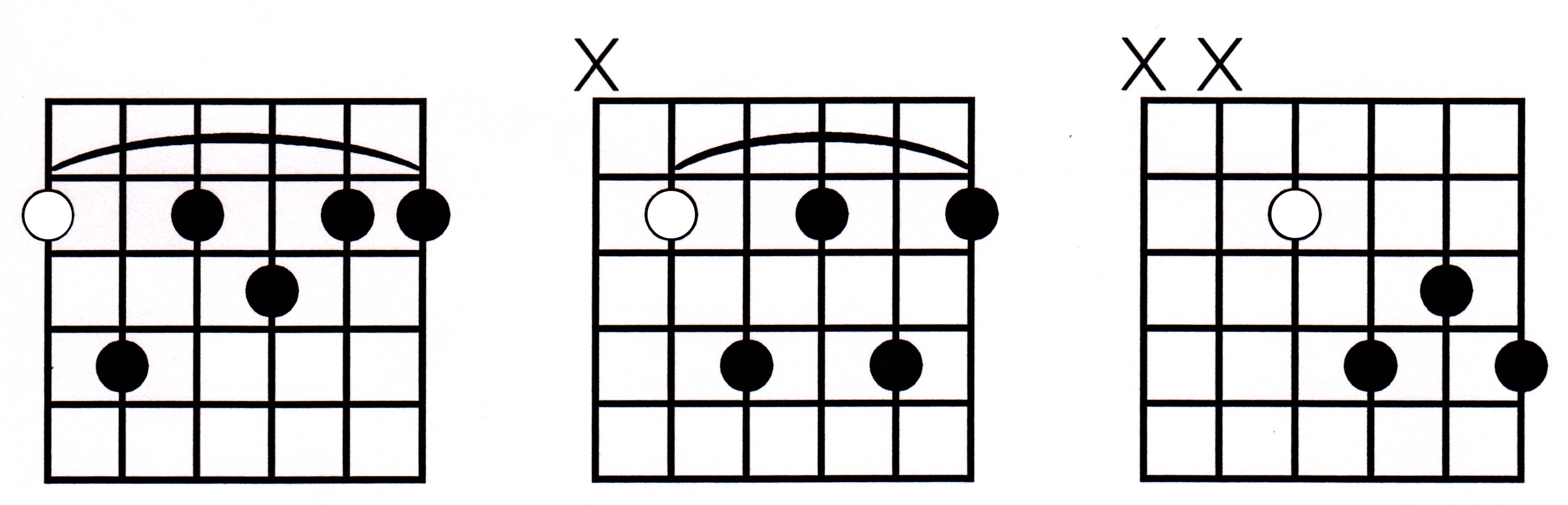

Next is a graphic of a minor chord, which is the "type", shown in three "forms", three different fingerings, based on a 6th, 5th and 2nd string root.

Again, the form changes as the root tone moves to a different string. The voicing may also change, depending upon the form played.

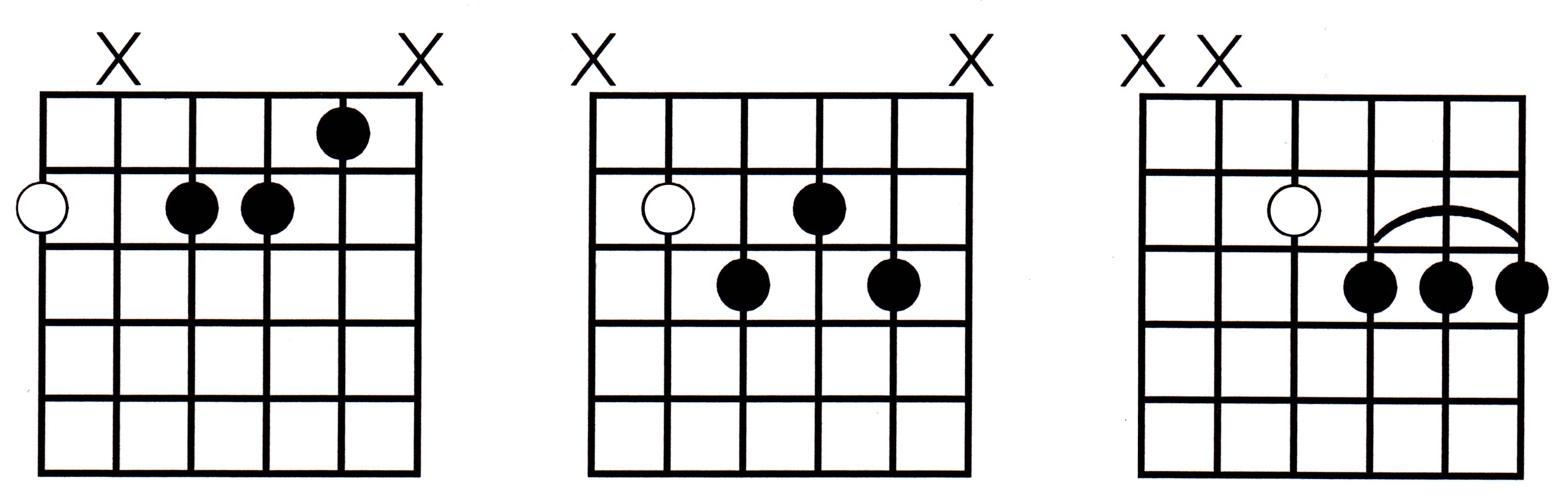

Let's look at the dominant 7 chord, which is the "type", shown in three "forms", three different fingerings, based on a 6th, 5th and 4th string root.

As you can see, in each case, because the root tone is located on a different string, the fingering changes.

Now we'll go a little deeper...

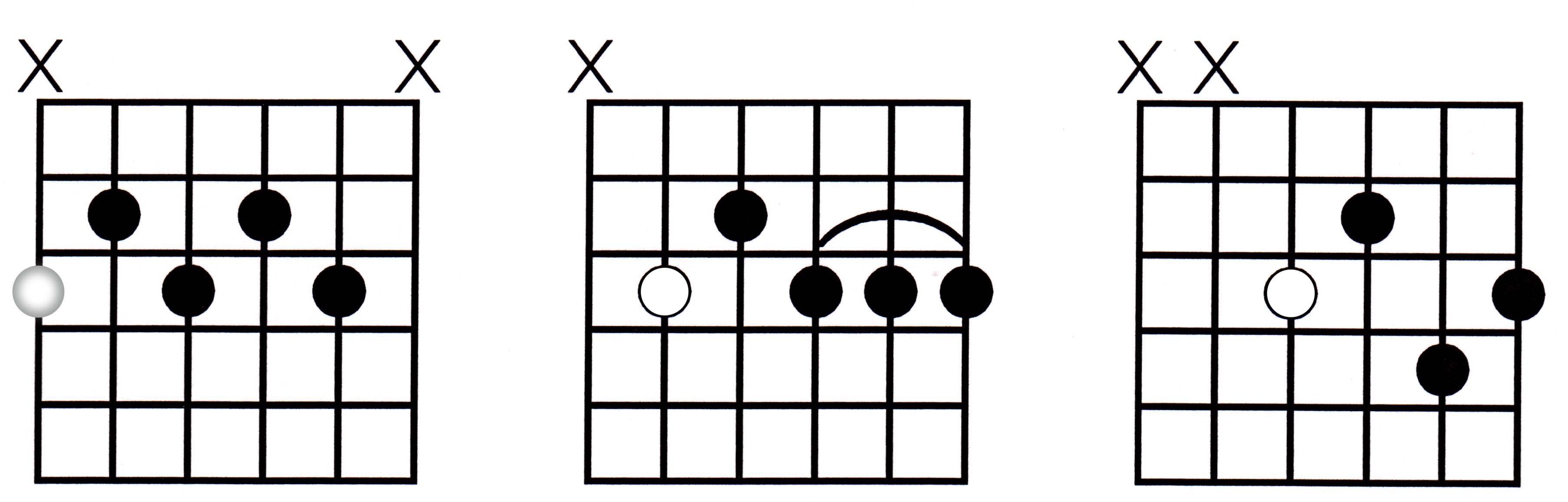

Even within the primary "types" (Major, minor, et al), there are specific fingerings (the form) for the variations. Check it out. Below is a graphic

looking at the type: mi7-5, also known as a half diminished, and three forms to play this chord, based on a 6th, 5th, and 4th string root respectively.

We've basically taken three chord forms you might already know (the mi7 chord type), and altered them slightly by flattening the 5 tone. This also requires a modification in how you play them. But that's part of the fun, right? Usually, you will employ the most practical, least troublesome approach to changing your fingering to accommodate the new information, which here is the flat 5 tone. Clue: use all four fingers in the first two examples, just two on the 3rd.

In the next graphic, let's look at a type: dominant 9, and three forms you can play, based on a 6th, 5th and 4th string root respectively.

Notice the grey circle in the first dominant chord. This is the root tone, which is not being played, making this a "rootless" variant form of the 9 chord type. And, yes, it looks exactly like another chord you just played. But when you change the root tone location, the relationship of the notes to the new root also change! This is another topic, of course, and may be covered later.

Through these few examples, you can clearly see the point of why we need to be specific in terminology when discussing chord types and forms. If we do not speak the same language, we remain in confusion until and/or unless we agree upon a standard practice to follow. That is the essence of music theory, to establish, to set down a specific way of describing the construction of musical elements, their application, expression, and all other aspects of the subject of music.

And when we all speak the same language, information flows more rapidly and with less confusion.

Okay, now shut off your computer and go play with some ideas.

See you next time.